1.4 Major Scales and Scale Degrees

7 min read•december 31, 2022

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

AP Music Theory 🎶

72 resourcesSee Units

Major Scales

Throughout history and up to the current era, different collections of pitches give us distinct types of music. When we arrange certain pitches in a specific ascending or descending pattern, we call that a scale. Western music is comprised of major and minor scales. There are many other types of scales that are used in other parts of the world.

The major scale is usually considered to have a a bright, cheerful sound and is used in many different styles of music, including classical, pop, rock, and jazz. However, major scales aren't only used for "happy" music (and minor scales aren't always for "sad" music). In classical music, there are some commonly accepted characteristics and moods for each major and minor scale. While you don't need to know this for the AP exam, learning these will help you as a musician, and they might generally be of interest. You can read more here.

The major scale has a long history, dating back to ancient Greek music theory. The Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras is credited with developing the concept of the major scale, which he referred to as the "diatonic" scale. In the Middle Ages, the major scale became a central part of Western music theory, and it has remained an important part of music theory and practice to this day.

How do you create a major scale? Let's first see what it looks like.

This is a C Major scale. It starts on a C, and ends on a C. A scale will always end on same note an octave higher (or lower). An octave is an interval of 8 pitches. We usually write major scales (and chords) using capital letters.

There is a very specific space between each pitch in a major scale: whole step-whole step-half step-whole step-whole step-whole step-half step. You don't really have to memorize this. You can just try deriving it from the C Major scale (the C major scale has no accidentals), or you can memorize which sharps and flats each major scale has. This is why the major scale is also known as the diatonic scale -- it is made up of five whole steps and two half steps, which are also known as "tones" and "semitones" respectively.

When we are writing in a certain key, for example C Major, we say that we are "in C Major." You can imagine all the notes that are a member of C Major as being in the key, and all the notes that are not a member of C Major as being out of the key. For example, D is in C Major, and D# is not in C Major. Another way to say this is to say that D is diatonic, and D# is chromatic.

Major Scale Degrees

The starting pitch is called the tonic. Each pitch is considered to be a degree of the scale, and each scale degree has a special name. For example, in a C Major scale, the first scale degree is C, the second scale degree is D, and so on. Each scale degree has a special name that is indicative of its role in the key.

Here are the degrees of the major scale:

- The tonic (also known as the "root" or "keynote") is the first degree of the scale and represents the starting point of the scale. It is the most important degree and is the basis for the tonality of the piece.

- The supertonic is the second degree of the scale. It is a whole step above the tonic and creates a strong sense of tonality.

- The mediant is the third degree of the scale. It is a whole step above the supertonic and is often used as a point of rest or resolution in a piece of music.

- The subdominant is the fourth degree of the scale. It is a whole step below the dominant and creates a sense of stability and rest.

- The dominant is the fifth degree of the scale. It is a whole step above the subdominant and creates a sense of tension and instability, which is resolved by returning to the tonic.

- The submediant is the sixth degree of the scale. It is a whole step below the mediant and is often used as a point of rest or resolution in a piece of music.

- The leading tone is the seventh degree of the scale. It is a half step below the tonic and creates a strong sense of tonality.

- The octave is the eighth degree of the scale and represents the end of the scale. It is a whole step above the tonic and creates a sense of completion and resolution.

Later on, you might get more intuition as to what these names mean. Most textbooks refer to both the base note and the corresponding chord in terms of the scale degree. For example, in a C Major scale, G Major will be the dominant chord. In major keys, the tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords are all major, and the supertonic, mediant, and submediant chords are minor. The leading tone will be diminished.

The major scale degrees are often abbreviated using Roman numerals, with uppercase numerals representing major chords and lowercase numerals representing minor chords. For example, the tonic of a C major scale would be represented as "I," the dominant would be represented as "V," and the submediant would be represented as "vi."

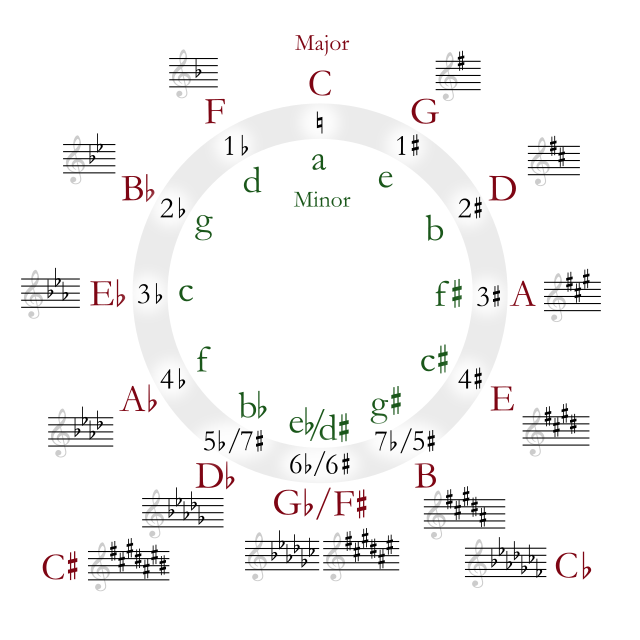

The Circle of Fifths

There is an easy way to remember which sharps and flats correspond to each major scale, without using the whole step-whole step-half step-whole step-whole step-whole step-half step pattern. For keys with sharps, you start by remembering that C major has no sharps, and G Major has one sharp (F#). If you go up a fifth from G, you get D. D Major has two sharps: F# and C#, which is just a fifth above F#. Similarly, A Major has 3 sharps, F#, C#, and G#!

For sharp keys, if you're given a key signature (the set of notes that are sharp) already, then you just go a half step above the last sharp and you will get the key. For example, the last sharp in D major is C#, and a half step above C# is D.

Next, let's talk about flat keys. Again, start by remembering that C Major has no flats, and F Major has one flat (Bb). This time, you go down by fifths. The major key that has two flats is a fifth below F, which is Bb, and the next flat is a fifth below Bb, which is Eb. If you are given a key signature in flats, then all you have to know is that the major key will be the second to last flat. The key that has 3 flats (Bb, Eb, and Ab) will be Eb Major, since it is the second to last flat.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: Can you name the pitches of the E Major scale? How many sharps of flats are there in the scale? Can you sing it back in your vocal range?

The idea of going up or down by fifths pops up a lot in music, and you can visualize this pattern by going clockwise or counterclockwise on a clock or a circle. If you keep going up by fifths, then you will eventually end up at the same note, and the same thing happens if you keep going down by fifths. This is called the circle of fifths.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

It's not really necessary to memorize this circle, but it is good to keep the image in the back of your mind. You will keep building on the idea of the circle of fifths as you learn more about music theory!

Writing Major Scale Key Signatures

A key signature is a set of symbols placed at the beginning of a musical staff that indicates the key of a piece of music. It tells the musician which notes to play sharp or flat in order to perform the piece in the correct key.

The key signature is written after the clef and time signature, and it consists of one or more sharp or flat symbols, each of which corresponds to a specific note on the staff. For example, a key signature with one sharp symbol on the F indicates that the note F should be played sharp throughout the piece. A key signature with two flat symbols indicates that the notes B and E should be played flat throughout the piece.

Key signatures are used in music to help musicians play in a specific key without having to constantly specify which notes should be played sharp or flat. This makes it easier for musicians to read and perform music, as they can focus on the other elements of the music, such as the melody and rhythm, rather than constantly having to look for accidentals (sharp or flat symbols).

Whenever you write a key signature, whether it is in Major or minor, there are a few things to keep in mind. First, the accidentals will always appear in the same order. You should also remember which line each accidental belongs on for bass clef and treble clef. Many musicians who are not used to reading in one of these clefs might put the accidentals in the key signature on the wrong lines. These details are not just style issues -- they are a matter of correctness -- so you should make sure you are confident in writing key signatures.

Usually, if you just practice writing music, you won't have to sit down and spend time memorizing these things: they will just enter your muscle memory.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🎵Unit 1 – Music Fundamentals I (Pitch, Major Scales and Key Signatures, Rhythm, Meter, and Expressive Elements)

🎶Unit 2 – Music Fundamentals II (Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture)

🎻Unit 3 – Music Fundamentals III (Triads and Seventh Chords)

🎹Unit 4 – Harmony and Voice Leading I (Chord Function, Cadence, and Phrase)

🎸Unit 5: Harmony and Voice Leading II: Chord Progressions and Predominant Function

🎺Unit 6 – Harmony and Voice Leading III (Embellishments, Motives, and Melodic Devices)

🎤Unit 7 – Harmony and Voice Leading IV (Secondary Function)

🎷Unit 8 – Modes & Form

📝Exam Skills

📆Big Reviews: Finals & Exam Prep

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.