Unit 6 Overview: Market Failure and the Role of Government

6 min read•december 23, 2022

dylan_black_2025

dylan_black_2025

AP Microeconomics 🤑

95 resourcesSee Units

Unit 6 Overview: Market Failure and the Role of Government

Have you ever been on a long trip with a group of people? Everyone is having fun and singing songs, and then you start regretting the numerous energy drinks🥤you drank thirty minutes ago. “Hey, can we pull into the next gas ⛽️ station? I really have to go.”

The group agrees that this is a wise choice, and you pull into the station to use the bathroom. The best way to describe the state of the bathroom🚽 is OMG!! or the scream emoji! Here’s the thing. The people before you have clean bathrooms at home, yet they will destroy a public restroom. Have you ever wondered why? Why are you more likely to litter in a public place than your own house? Why are corporations and countries willing to dump their trash into the ocean and not in their own land? Why aren’t companies willing to give out cancer treatment 💊 for free? Unit 6 is all about when the free market fails to produce at the socially optimal levels. When the market fails, who comes to the rescue? The Government, which taxpayers fund (i.e., you!).

⚠️ Warning: There is a substantial economic debate about how much the government should be involved in market failure, with some arguing the government should never intervene at all. Brilliant people are looking at the same data and coming up with very different theories and conclusions. The good news for you is that the AP® exam will not ask you about the “shoulds” or anything about your opinion about this economic debate, so if you’re pressed for time, focus on the objective bits. If you want to see what all the fuss is about, here’s an earworm 🐛 of a song that gives a good breakdown of two sides: Emergent Order- Fight of the Century. Otherwise, focus on the “hows” of this section and save the ponderings of what should be for university 🎓

6.1 Socially Efficient and Inefficient Market Outcomes

In Unit 6, we need to distinguish between what is good for an individual and good for a group of individuals. We’ve been looking at individuals and businesses for Units 1-5. Here is where the Micro curriculum starts overlapping a tiny bit with Macro because we are now adding the OG into the mix: the government.

In 6.1, you will learn how efficiency in a market can be applied to society in what we call social efficiency. In a completely free market, the amount made of a specific good or service (the socially optimal quantity) will be where the marginal social benefit (MSB) of consuming the good meets the marginal social cost (MSC) of producing the good. This sounds logical and fair, right? A society should produce where demand equals supply.

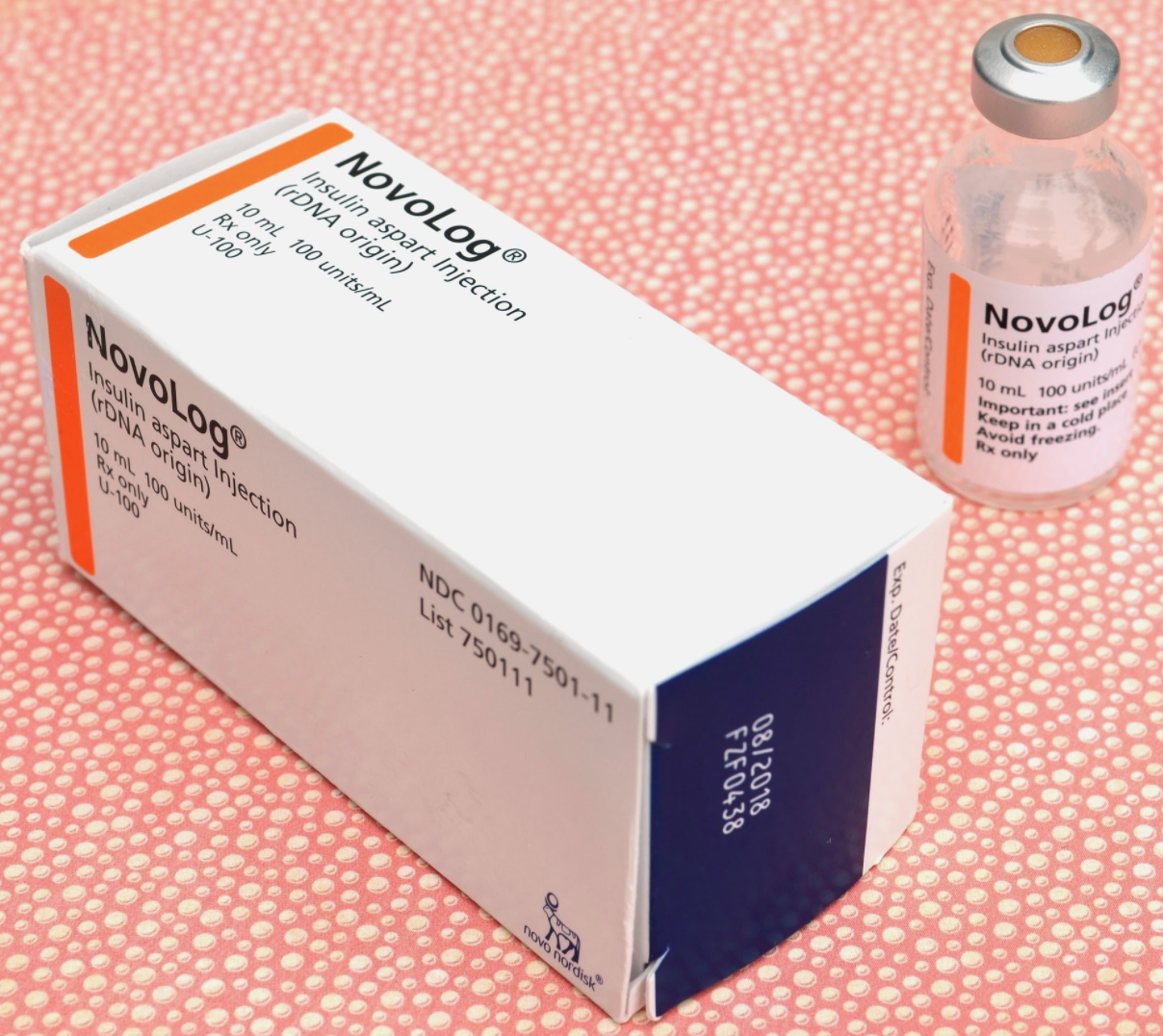

Now, let’s look at an actual product, insulin. The price for insulin without insurance in the USA can run from $100 to $250 a vial. What happens to a person who cannot pay that price? When we look at the demand curve made from the MSB, we are tempted to forget that the data points on the bottom half of the demand curve of MSB are people who would be willing and able to demand insulin at a lower price. The/ market does not allocate life-saving medication to them unless they can pay for the drug. Yet, if we decrease the price, we will have a shortage of insulin, and if we increase the price, we will have a surplus of it.

This is one of the reasons Economics gets “the dismal science” label 🏷 We can’t have perfection. Still, we at least can aim for a socially efficient market outcome (MSB=MSC) to meet a socially optimal quantity even when it means people are left without the ability to afford a product.

6.2 Externalities

In 6.2, we take the concept of social efficiency and examine what happens when a private individual (or a group of them) is not paying the full cost of their demand. It sounds complex, but you know it.

Let’s say your next-door neighbor wants to take opera lessons. They pay the voice teacher forty dollars for a two-hour lesson. This should be a fair trade, but no one seems to notice that the screeching 🗣 keeps you from working during that two hours. You will lose two hours of business for which no one will compensate you because someone else made a purchase. This is one example of a market failure called an externality. The market has failed to produce the socially optimal amount of opera lessons, and now you are paying for a choice you did not have agency to make 😢

There are negative externalities and positive externalities for both consumers and producers. Be ready to identify both types for the exam. And know how to graph them!

6.3 Public and Private Goods

Another type of market failure is public goods. An easy example to remember is public school. Taxpayers fund public schools with money allocated by the government, but why? What would happen if the only schools around were private and funded by tuition? Many children would not be able to go to school because they would not afford it. Private schools, and every business in the private sector, can reject a student who cannot pay the tuition (exclusionary). If one person is benefiting from the education, someone else is not (rivalrous). Society benefits from more children getting an education, so the government has schools that allow you to attend even if you can’t pay taxes (non-exclusionary), and just because one person attends school it doesn’t keep out another person (non-rivalrous). Thus, the importance of public education!

6.4 The Effects of Government Intervention on Different Market Structures

What do we know about economics? For every choice, there is an opportunity cost. Government intervention is not an exception to this rule, and many political debates are economical. For example, should citizens access the internet 📡 even if they cannot pay for it? Is having the internet that important to society? If so, how do we as a society minimize costs while still providing the producer a chance to earn a living wage? In this section, you will see how markets look at an unregulated quantity, at a fair return quantity, and a socially optimal quantity. There are pros and cons to each, and society must balance the marginal social benefits to the marginal social costs to make an informed decision.

6.5 Inequality

The very last section in AP Micro examines how we measure the allocation of a nation’s wealth. Using a Lorenz Curve, we can see the wealth of certain sections of society within a country. The Gini coefficient shows us how wealth is distributed and allocated. The closer the coefficient is to 0; the higher the number, the fatter the banana on the Lorenz Curve. One way to redistribute wealth is through taxes: progressive, proportional, and regressive taxes.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

💸Unit 1 – Basic Economic Concepts

📈Unit 2 – Supply & Demand

🏋🏼♀️Unit 3 – Production, Cost, & the Perfect Competition Model

⛹🏼♀️Unit 4 – Imperfect Competition

💰Unit 5 – Factor Markets

🏛Unit 6 – Market Failure & the Role of Government

📝Exam Skills: FRQ/MCQ

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.